Estimation at Maxwell

As software engineers, we have a lot of strengths, but our kryptonite is probably estimation. A running joke on a former team early in my career was that any request will take about 2 weeks. 2 weeks is long enough to seem like enough time to finish a project that you basically understand but haven’t dug in to. And it is short enough to satisfy those who inevitably want something now and get them off your back. So just tell everyone 2 weeks and get on with it. Great! Until it catches up with you…

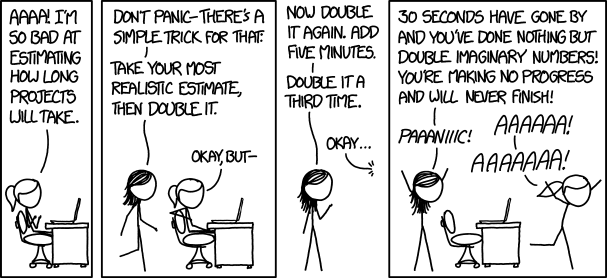

As always, xkcd describes it perfectly - https://xkcd.com/1658/

The natural reaction to estimations being wrong is to think “we just need to do more and better planning.” So days or weeks are spent (wasted) in extremely detailed planning, and the project takes forever, and the estimates are still wrong. You might think this sounds like the dreaded waterfall method, but I’ve seen teams that swear they are doing “agile” of some flavor fall into this trap.

The reality is that many challenges and details of a project can only be uncovered by diving in. So, maybe we should declare “estimation bankruptcy”, skip planning, and just dive in? That won’t work well either. As the saying goes, “if you fail to plan, you plan to fail”.

With multiple product lines and product development teams at Maxwell, the need for better planning and estimating is essential to both developer happiness and growth of the business. Furthermore, the approach we take to planning and estimating needs alignment and consistency across teams and projects. The following describes our conclusions after quite a lot of discussion and debates.

Points are for Planning

Points have a role to play in planning, and we think of them as a metric to help us with estimation. Points are assigned to stories based on complexity. By giving a point estimate based on complexity after understanding the fundamentals of a feature, we avoid the pitfalls of overplanning. Do enough planning to break down the project into fundamentals, and then give it a point-value based on complexity and/or remaining unknowns. You are likely pretty familiar with this process - the fibonacci sequence (1,2,3,5,8,13) and variations of it are popular ways to force more complex projects to have bigger estimation to compensate for an engineers’ natural optimism.

All product development teams at Maxwell share the approach of using story points for estimation. Adding up all the points completed during a 2-week Sprint gives us a sense of the velocity of a Sprint.

Then, using the anchor of the average Sprint velocity of a team, we can estimate how long a project (a project is usually an Epic which is made up of one or more stories) will take, or how much work can likely be completed in a Sprint

This approach of calibrating our estimates to previous work has objectively helped us align and improve our ability to estimate as a product development team far more consistently than before.

However, like any framework, there are nuances to consider. To document those nuances, we agreed on the following tenets of estimation using points.

Maxwell’s Tenets of Estimation using Points

Once made, Estimates should not change

So what do we do when we find out that some (all?) of our team’s estimates were crap? Shouldn’t we fix them? NO! That is the point! Don’t change them! At the end of the sprint you want to be able to say “We can do XX points of very poorly estimated stuff”. If you change an estimate, the velocity at the end of a sprint can no longer be applied to your backlog of work. The key is that you are bad at estimates in a consistent way. Find your estimation zen by just letting it go, accepting that you can never be good at estimation.

Okay… but what if something really blows up: you discover that much more work is actually going to be needed because something big was missed in planning – or someone (certainly not product managers) insists that the scope of the project must expand to more than planned? In this case you need to create and estimate new issues, then talk as a team about how that will impact your sprint and roadmap. Either you bump other stuff out of the sprint, or you put the new stuff into the next.

Estimates are not specific to individuals

Estimates are used for delivering work consistently, not to measure productivity. It’s normal for two engineers on the same team to complete 3 points at different speeds. Remember that we are bad at estimation, so one engineer’s 3 points of work may have turned out to be much more significant than another’s, or 2 engineers may have different experience and productivity levels. Point estimates value is in the aggregate, averaging out the differences in individuals and the unknown of various tatsk.

A common mistake is to change the estimate for the individual, or have individuals estimate their own work. This results in things like making estimates smaller for more experienced engineers or bigger for junior engineers, or smaller for someone who has worked in that code before because they will be able to “get it done faster”.

Making individual estimates also incentivizes individuals to inflate the estimation of issues, especially if they think they will be the one doing the work, which makes estimation less consistent.

If estimation is individualized, the aggregate velocity of a team becomes meaningless and useless for team planning. How do you interpret velocity and use it to plan the next sprint if the scale for each issue is different?

Individual estimation also incentivizes team members to compare their output of points to others on the team, which can be a very unhealthy dynamic. Remember that points are a team planning tool, not individual. Someone might spend an entire sprint on a 2 point task - because the team did a poor job of estimating it. That individual should not be punished for that, but the team’s velocity would be impacted, and the team’s planning would need to accommodate.

Estimates must be made as a team

Group estimating reinforces that estimates are not specific to who does the work. It also allows everyone the opportunity to surface risks and unknowns, helps engagement, and increases knowledge-sharing.

If team members disagree on an estimate, it is a sign that there are additional unknowns or complexity that has not been identified. There is a lot of value in continuing to discuss and align on the team’s estimate calibrations.

Estimates are specific to a team, and can’t be compared across teams

Points might be pretty different from one team to the next even in the same company. What may be a small task in one codebase could be a larger task in another due to tech debt or additional requirements to support existing functionality. Therefore, it doesn’t make sense to compare points across teams. Points should be reviewed during each team’s retros and planning to track consistency, plan effectively, and surface process issues worth addressing. Issues with alignment on estimates should be addressed using the estimate calibrations for the team.

Estimates should not be shared outside of product and engineering

Finally, points will have a specific meaning and calibration to a team, but should not be shared with other departments. Estimates require too much context like team composition and project complexity to be readily useful to the rest of the business. Instead, we focus on the deliverables that the business expects and report on milestones towards those deliverables. By keeping estimates as a tool within product development , we can focus on improving our process without worrying about the perception of points being completed.

Conclusion

In May of 1804 the Lewis and Clark expedition set out from St. Charles Missouri on a 3 year journey to explore the Louisiana Purchase and find a route to the pacific ocean through the pacific northwest. There were no maps of the area they planned to travel through, and very little information about what challenges they would encounter. All they really knew is that many people thought if they followed the Missouri river to its source, it would be close to the source of the Columbia river and they could follow that to the Pacific.

If you were Lewis or Clark, how would you plan and prepare for such an expedition? There was no way to be sure about anything at the time: distance, obstacles, dangers, or availability of food. Lewis and Clark gathered whatever little information there was available about the area, recruited a talented team of frontiersmen, and plenty of supplies. Then, they set off.

They faced and overcame enormous challenges that they had no idea they would encounter. They did this by adapting what they had, and adjusting as they went to new information. They found that there is a massive mountain range between the Missouri and Columbia rivers. But they overcame and their expedition was enormously successful, they produced the first maps of the area, established diplomatic relations with many native tribes, made scientific discoveries, and more.

Maybe they could have explored a little at a time, sending scouts out to various parts and waiting for them to return. But if they had waited for more information, someone else would have done it before them - quite literally. President Thomas Jefferson wanted the U.S. to beat the Spanish, French and British to the northwest in order to lay claim.

For too many software projects, it seems as if we are trying to build a detailed map before we start a project that can only be created by exploring it. At Maxwell, we take the “Lewis and Clark approach” to product development. We gather talented people, supplies, and whatever knowledge is available, then we set off. Using our Tenets as our guiding principles, we can consistently apply that approach across all projects and teams.