Elegant releases: Reduce thrash and increase developer happiness

Continuous integration and deployment is a core tenet of agile development and fundamental to a high-performing technology organization, as research by Gene Kim and colleagues have shown[1]. Deploying frequently results in smaller releases, more frequent updates for your users, quicker feedback from real users, and a tighter feedback loop between business decisions and shipped products.

The worst enemy of continuous deployment is a broken build. The larger the engineering team, the worse it is. Incompatible code and inconsistent DB state will trickle down your development process and cost engineers time and your business money. I believe a strong understanding of the basics and a standard playbook to follow are the most effective tools at our disposal to avoid common pitfalls around release issues.

Below, I will outline the release cycle and common pitfalls with a focus on Maxwell’s preferred stacks of Ruby + Javascript apps hosted on Heroku and AWS. I’ll also describe some guidelines to follow to plan safe, graceful releases and migrations.

Release Cycle Steps 1 & 2

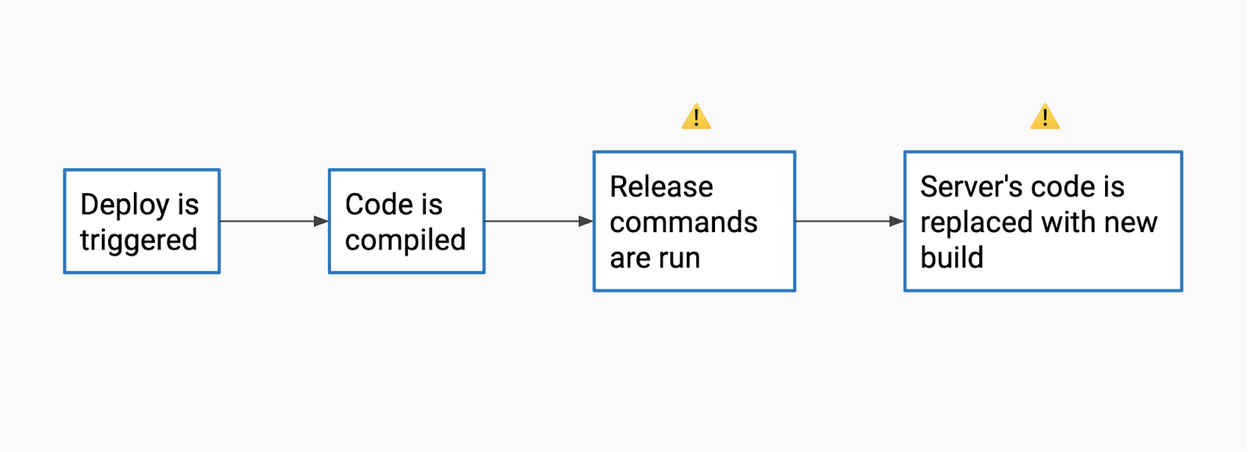

Many modern apps follow this 4-step deploy cycle (of course, your setup may vary).

Steps one and two are safe for most apps. You click on a deploy button or execute a CLI command, perhaps from your CI tool, which kicks off the build process for your new release. This happens on a release server, so nothing should be changing on your production servers yet.

A build process can vary widely, but with Ruby we don’t have much to worry about besides running bundler and fetching dependencies. For our frontend, we run rails assets:precompile which ends up preparing our Javascript assets with webpacker.

Step 3 - Danger Zone 1 - Executing release commands

Release commands are usually tasks that prepare data for the new code. Some example of this are:

- Database migrations

- Uploading build assets to external sources

- Preparing new environment configurations

This is a sensitive step because your tasks will be executed against data sources that are being used by your production app. For example, if you remove a column from your DB table, any live code that depends on that column will immediately begin to fail. Changes must be safely compatible with the current, old code as well as the new code that will be released in the next step.

Step 4 - Danger Zone 2 - Deploying code to production

Finally, your new build is pushed to production servers. In AWS, this happens when we update our ECS task definitions and refresh the cluster. In Heroku, the process is a combination of some helpful tools around releases like Preboot and the Release Phase as well as their own secret sauce. While these tools are helpful, they don’t eliminate the need for planning safe releases.

The main risk here is that your new code will begin serving requests as soon as the first new server initializes. If your code depends on a new table and you haven’t created it yet on your production app, that code will immediately begin to fail.

Additional considerations

Besides these two danger zones, here’s a few other things you should consider before kicking off any production deployments:

Does your release contain long-running data migrations?

A common task engineers perform is migrating data to a new column, or adding a new calculated field to a table. Since Rails loves sharp knives and provides you with full ActiveRecord in migration files, it can be tempting to just write a loop and populate a bunch of records with .create.

This is dangerous! Without knowing exactly how long a migration can take, you run the risk of timing out your release commands or consuming all available resources and failing the build. Depending on your configuration and whether you moved this outside of a transaction, this could leave you with an inconsistent DB state.

Does your release hold a transaction, add indices or locks, or perform other heavy table operations?

It’s also important to be aware of expensive database operations like adding indices or changing column types. Transactions and locks can prevent new data from being written to your DB and results in lost data.

Resources exist [2] to help identify potentially risky migrations as well as tools like the strong_migrations gem which we use as part of our CI at Maxwell.

Is your release affecting a distributed system?

Releasing changes to a single application is one thing, but if you’re updating part of a larger system you’ll need to consider the downstream effects.

The below release process can also be applied to multi-system releases, while noting that there will generally be many more releases involved in order to gracefully transition each system safely while it is still interacting with other apps.

1-2-3: A slow, safe release process

In this section, we’ll take a common scenario and describe the releases necessary for a safe migration. The request is: move the email column from the user table to the user_details table. Keep in mind that there are existing emails in the original table.

My rule of thumb is: The more explicit, smaller steps, the safer the release (to a point!). The more you break things down into parts, the less likely any release will result in a broken build or put your application into a messy state that requires manual intervention. If you have a reliable CI/CD pipeline, more releases can also be as easy as merging pull requests in your repository of choice.

Keeping that in mind, here’s a plan to release this change:

Release 1 - Prepare our new column, begin data synchronization, and asynchronously prepare all data

First and foremost, we’ll want to create a new email column on the user_details table. Stopping here would mean no data in the new column and nothing for our code to use.

To ensure data is fully synced by the time the second release comes along, we’ll want two things:

- Modify any code that previously set

emailon theusertable to also update theuser_detailstable. By updating both, we will make sure that any updates after our population scripts are reflected in the second table. - An asynchronous task to back-populate emails in the new table. Based on our additional considerations, we should not be populating large amounts of data in the migration itself. So a typical approach here would be to ship a rake task or other script that can be run on the server once the release goes out.

Once this release is deployed, we can execute our data population task/script. Since it lives outside of a migration, we can handle any long-running tasks by splitting work up or putting it in a background queue. Once the data population is done, we are done with the first release and our DB is in a state where it is ready to receive calls from the new code.

Release 2 - Updates to the application code

Next, we’ll update anywhere that was previously referencing user.email to user.user_details.email. We can also remove our glue code which was updating user.email since there will no longer be any code referencing it.

Since your two columns are in sync, this code change is safe to release.

Release 3 - Dropping old columns, code, and cleanup

At this point, our application should be running the way we want it to. We added a new column and populated it both asynchronously and in real-time, and then released code changes to use our new column.

It is now safe to drop the old user.email column since code is no longer using it.

Fin

The first time people see all these steps, a common reaction is “dang, that’s a lot of steps”! I agree, however there is a real trade off between the complexity caused by splitting up releases vs. the risk associated with all-in-one releases. Investing in your CI/CD will also allow large data migrations to become manageable to more developers by simplifying releases to merging a pull request.

Greenfield projects and smaller startups have a higher risk tolerance and may find it acceptable to ship quick and break releases every once in a while. As you scale, quality requirements will increase and downtime will result in more and more headaches for you and your customers. Simple strategies around how to plan clean releases with multiple people releasing code to production helps us avoid common issues which can have domino effects on an entire team.